Among all the regions of the world, the East remains an elusive frontier for Western products and services seeking to expand there. Many entrepreneurs have failed, unable to demonstrate the flexibility needed to navigate markets governed by deeply different logics. Today, we will focus on the reasons behind these failures, specifically in two key territories: mainland China and the Arab world.

The New New Continent

Since its meteoric economic rise, mainland China, with its 1.4 billion inhabitants, has disrupted global trade dynamics. This surge has revealed a market of consumers with growing purchasing power, eager for foreign experiences and products. However, this rise has caught many multinationals off guard. Too often, they underestimate the scale of the Chinese challenge. Companies already established managed to anticipate and position themselves, capturing crucial market shares. But for newcomers, the Chinese market feels like a wall. These latecomers inevitably hit a ceiling, repeating the same mistakes: a failure to grasp the nuances of a deeply coded culture.

“The Chinese market feels like a wall. These latecomers inevitably hit a ceiling, repeating the same mistakes: a failure to grasp the nuances of a deeply coded culture.”

Translating China: Design and Language

Translation in China goes far beyond words. It touches on cultural and technological aspects often imperceptible to a Western eye. The Chinese digital ecosystem perfectly illustrates this difference. While some Chinese apps have made their way into our daily lives, it often comes at the cost of a complete overhaul of their interface to meet Western standards. In China, however, the user experience follows a logic that confounds outsiders, reflecting fundamentally different priorities and practices.

Technological transition in China occurred much later than in the West. When digital technologies emerged, they were directly optimized for mobile. While the West first developed websites for computer screens, China skipped this step, propelling its users straight into the smartphone universe. This leap reshaped usage: instead of traditional website navigation, Chinese users rely heavily on so-called “Everything Apps.” These platforms centralize a multitude of services. Want to visit a museum? A simple integrated mini-program allows you not only to check schedules but also to book a ticket without manually entering your payment details. Everything is integrated, simplified, streamlined.

This reliance on “Everything Apps” rests on a fundamental pillar: trust. Chinese society, largely communal, strongly values social cohesion. Although awareness of data protection issues is lower than in the West, financial security remains a top priority. To meet this demand, these apps incorporate alternative and omnipresent payment systems. Users rely on them to pay for groceries, movie tickets, or even flights. This trust is based not only on the robustness of the technical infrastructure but also on close government oversight.

These specifics are also reflected in app design. Unlike Western standards, which prioritize clean interfaces with clear spacing and distinct calls to action, Chinese apps adopt a radically different approach. Their interfaces are dense, almost saturated with information. This is partly due to the nature of the Chinese language, whose ideographic system allows for a lot of information in few characters. Additionally, Chinese can be read in multiple directions, increasing visual density.

“In the West, red is often associated with danger or prohibition, while in China, it symbolizes prosperity and serenity.”

The color palette differs as well. In the West, red is often associated with danger or prohibition, while in China, it symbolizes prosperity and serenity. These visual codes, deeply rooted in local culture, may confuse Western users, for whom these interfaces might seem chaotic. However, this is not disorder but a different organization, tailored to specific cultural expectations.

Tesla: A Technological and Cultural Symbiosis

Tesla, though American, has successfully bridged the gap to China’s digital culture. From the outset, the company integrated local applications like QQ Music and Bilibili, allowing users to access their favorite content directly from their vehicle. In China, where streaming and social platforms are ubiquitous, this integration was seen as essential, embedding Tesla in the digital daily lives of its customers.

Tesla also refined voice commands in Mandarin, considering linguistic nuances and local needs. This allowed for a natural, seamless interaction with the vehicle, a major asset for a tech-savvy audience. Moreover, Tesla incorporated local payment systems like WeChat Pay and Alipay, simplifying access to charging and maintenance services. This attention to detail in both interface and services demonstrates a deep understanding of cultural expectations.

Airbnb: A Poorly Translated Experience

Airbnb, on the other hand, struggled to adapt. Its interface, while functional in the West, failed to meet Chinese digital habits. Unlike local expectations, Airbnb initially lacked a smooth instant messaging system, making communication between hosts and guests cumbersome. Chinese users, accustomed to fast, direct communication, opted for local alternatives like Tujia.

Airbnb was also slow to offer suitable payment options. In a market where Alipay and WeChat Pay are ubiquitous, this initial omission was a significant barrier. Even after introducing these options, the user experience lagged behind, missing interactive elements and local recommendations that make its competitors successful.

Success in China requires much more than mere linguistic translation. It involves immersing oneself in a world of practices, symbols, and deeply distinct values. Tesla shows that a company can thrive by reinventing its interfaces to align with a local ecosystem, while Airbnb highlights the pitfalls of insufficient adaptation.

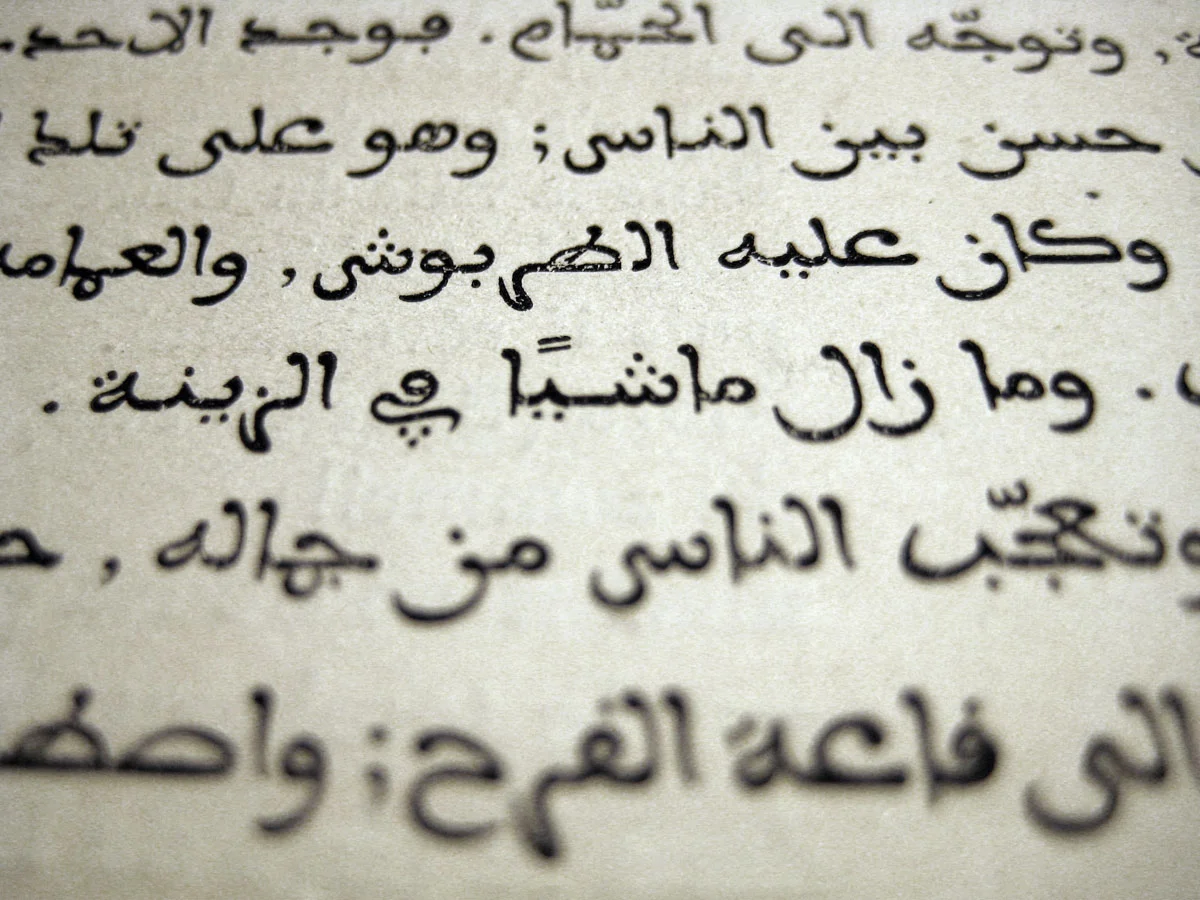

Translating the Arab World: RTL and Ubisoft

The Arab world, with its 22 countries and hundreds of millions of speakers, presents unique challenges for localization in the tech and cultural industries. Right-to-left (RTL) writing and the use of transliteration are critical technical considerations. However, beyond these technical challenges, cultural misunderstandings and persistent stereotypes often hinder the adaptation of Western products and services in this region.

Ubisoft, the publisher of the famous Assassin’s Creed franchise, has often drawn inspiration from the Arab world for its games. Titles like Assassin’s Creed and Prince of Persia immerse players in environments inspired by the Middle East, with rich architectures, cultures, and stories. However, despite this cultural immersion, these games were not initially translated into Arabic, limiting their accessibility for Arabic-speaking players.

“Offering games inspired by the Arab world without making them available in the local language can be seen as cultural appropriation.”

This lack of localization raises several issues. Accessibility is restricted for Arabic-speaking players, even those fluent in other languages, who may struggle to fully grasp the narrative and cultural nuances without proper translation. Offering games inspired by the Arab world without making them available in the local language can be seen as cultural appropriation, where cultural elements are used without true engagement with the original audience. The Arab video game market is rapidly expanding. Failing to localize these games in Arabic means missing out on a significant potential audience.

The reasons for this lack of localization are manifold. Technical challenges in adapting interfaces for RTL writing require a complete redesign of menus and navigation systems. Video games, with their complex interfaces, make this adaptation even more challenging. Localization goes beyond mere text translation. It includes dubbing, adapting graphics, and complying with local cultural norms, which represent a substantial investment. Companies may underestimate the size or potential of the Arabic-speaking market, justifying the lack of investment in localization.

However, Ubisoft has recently taken steps to address this gap. With the release of Assassin’s Creed Mirage, the company not only set the action in 9th-century Baghdad but also offered full Arabic localization, including dubbing and user interface. This initiative reflects a recognition of the importance of the Arabic-speaking audience and an effort to provide an authentic, immersive experience.

Conclusion

The export of Western products and services to markets like mainland China and the Arab world highlights a frequently ignored truth: the world is not a homogeneous extension of the West. While globalization has indeed fostered economic interconnection, it has not erased cultural, linguistic, and technological particularities. Yet a persistent belief in the West assumes that innovations, standards, and practices from Europe or America can apply everywhere without major adaptation.

This bias stems from a self-centered view, where the West is perceived as the epicenter of global economic and cultural dynamics. It overlooks the fact that emerging markets, in full expansion, operate under their own logics, shaped by distinct values, practices, and priorities. This belief in the supposed universality of Western models leads to strategic mistakes.

Examples like Tesla, Airbnb, Ubisoft, and other major players in the gaming industry show how misleading this simplistic vision can be. While Tesla adapted in China by integrating local specificities, Airbnb failed by clinging to a universal notion of user experience. Ubisoft, for its part, long ignored the importance of localizing its games for the Arabic-speaking audience, even as it heavily borrowed from the region’s aesthetics and imagination.

Localization is not just about translation; it is about reinvention. Interfaces must be rearranged, visual norms reinterpreted, and user expectations incorporated to meet deeply rooted needs in specific cultural contexts. In China, “Everything Apps” centralize services in a way unimaginable in the West, radically changing how users interact with digital platforms. In the Arab world, RTL writing and the diversity of local dialects necessitate rethinking ergonomics and linguistic interactions.

What’s at stake goes beyond mere commercial success. It involves a process of decentering, an effort to understand that the world does not align with a single model. The supposed Westernization of markets is merely a façade. Behind it, complex ecosystems develop, often parallel to Western logics. This is where the true dynamic of globalization lies: not in homogenization, but in coexistence and mutual adaptation.

The key to success today lies in humility. Accepting that other markets do not follow rules established by the West means recognizing that these regions are not lands to conquer but worlds to understand. Tesla and Ubisoft, through their recent efforts, show that building bridges is possible. But these examples remain rare in a landscape still dominated by strategies overly centered on Western perspectives.

“The world is not Westernizing; it is diversifying. And within this diversity lies the future of innovation and growth.”

It’s time for companies to rethink their approach: the world is not Westernizing; it is diversifying. And within this diversity lies the future of innovation and growth.

- yaro